Series Index

Python and Go: Part I - gRPC

Python and Go: Part II - Extending Python With Go

Python and Go: Part III - Packaging Python Code

Python and Go: Part IV - Using Python in Memory

Introduction

In the previous post we compiled Go code to a shared library and used it from the Python interactive shell. In this post we’re going to finish the development process by writing a Python module that hides the low level details of working with a shared library and then package this code as a Python package.

Recap - Architecture & Workflow Overview

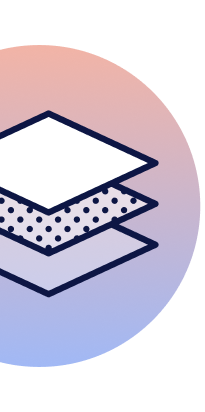

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the flow of data from Python to Go and back.

The workflow we’re following is:

- Write Go code (

CheckSignature), - Export to the shared library (

verify) - Use ctypes in the Python interactive prompt to call the Go code

- Write and package the Python code (

check_signatures)

In the previous blog post we’ve done the first three parts and in this one we’re going to implement the Python module and package it. We’ll do this is the following steps:

- Write the Python module (

checksig.py) - Write the project definition file (

setup.py) - Build the extension

Python Module

Let’s start with writing a Python module. This module will have a Pythonic API and will hide the low level details of working with the shared library built from our Go code.

Listing 1: checksig.py

01 """Parallel check of files digital signature"""

02

03 import ctypes

04 from distutils.sysconfig import get_config_var

05 from pathlib import Path

06

07 # Location of shared library

08 here = Path(__file__).absolute().parent

09 ext_suffix = get_config_var('EXT_SUFFIX')

10 so_file = here / ('_checksig' + ext_suffix)

11

12 # Load functions from shared library set their signatures

13 so = ctypes.cdll.LoadLibrary(so_file)

14 verify = so.verify

15 verify.argtypes = [ctypes.c_char_p]

16 verify.restype = ctypes.c_void_p

17 free = so.free

18 free.argtypes = [ctypes.c_void_p]

19

20

21 def check_signatures(root_dir):

22 """Check (in parallel) digital signature of all files in root_dir.

23 We assume there's a sha1sum.txt file under root_dir

24 """

25 res = verify(root_dir.encode('utf-8'))

26 if res is not None:

27 msg = ctypes.string_at(res).decode('utf-8')

28 free(res)

29 raise ValueError(msg)

Listing 1 has the code of our Python module. The code on lines 12-18 is very much what we did in the interactive prompt.

Lines 7-10 deal with the shared library file name - we’ll get to why we need that when we’ll talk about packaging below. On lines 21-29, we define the API of our module - a single function called check_signatures. ctypes will convert C’s NULL to Python’s None, hence the if statement in line 26. On line 29, we signal an error by raising a ValueError exception.

Note: Python’s naming conventions differ from Go. Most Python code is following the standard defined in PEP-8.

Installing and Building Packages

Before we move on to the last part of building a Python module, we need to take a detour and see how installing Python packages work. You can skip this part and head over to code below but I believe this section will help you understand why we write the code below.

Here’s a simplified workflow of what’s Python’s pip (the cousin of “go install” in the Go world) is doing when it’s installing a package:

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows a simplified flow chart of installing a Python package. If there’s a pre-built binary package (wheel) matching the current OS/architecture it’ll use it. Otherwise, it’ll download the sources and will build the package.

We roughly split Python packages to “pure” and “non-pure”. Pure packages are written only in Python while non-pure have code written in other languages and compiled to a shared library. Since non-pure packages contain binary code, they need to be built specially for an OS/architecture combination (say Linux/amd64). Our package is considered “non pure” since it contains code written in Go.

We start by writing a file called setup.py, this file defines the project and contains instructions on how to build it.

Listing 2: setup.py

01 """Setup for checksig package"""

02 from distutils.errors import CompileError

03 from subprocess import call

04

05 from setuptools import Extension, setup

06 from setuptools.command.build_ext import build_ext

07

08

09 class build_go_ext(build_ext):

10 """Custom command to build extension from Go source files"""

11 def build_extension(self, ext):

12 ext_path = self.get_ext_fullpath(ext.name)

13 cmd = ['go', 'build', '-buildmode=c-shared', '-o', ext_path]

14 cmd += ext.sources

15 out = call(cmd)

16 if out != 0:

17 raise CompileError('Go build failed')

18

19

20 setup(

21 name='checksig',

22 version='0.1.0',

23 py_modules=['checksig'],

24 ext_modules=[

25 Extension('_checksig', ['checksig.go', 'export.go'])

26 ],

27 cmdclass={'build_ext': build_go_ext},

28 zip_safe=False,

29 )

Listing 2 shows the setup.py file for our project. On line 09, we define a command to build an extension that uses the Go compiler. Python has built-in support for extensions written in C, C++ and SWIG, but not for Go.

Lines 12-14 define the command to run and line 15 runs this command as an external command (Python’s subprocess is like Go’s os/exec).

On line 20, we call the setup command, specifying the package name on line 21 and a version on line 22. On line 23, we define the Python module name and on lines 24-26 we define the extension module (the Go code). On line 27, we override the built-in build_ext command with our build_ext command that builds Go code. On line 28, we specify the package is not zip safe since it contains a shared library.

Another file we need to create is MANIFEST.in. It’s a file that defines all the extra files that need to be packaged in the source distribution.

Listing 3: MANIFEST.in

01 include README.md

02 include *.go go.mod go.sum

Listing 3 shows the extra files that should be packaged in source distribution (sdist).

Now we can build the Python packages.

Listing 4: Building the Python Packages

$ python setup.py bdist_wheel

$ python setup.py sdist

Listing 4 shows the command to build binary (wheel) package and the source (sdist) package files.

The packages are built in a subdirectory called dist.

Listing 5: Content of dist Directory

$ ls dist

checksig-0.1.0-cp38-cp38-linux_x86_64.whl

checksig-0.1.0.tar.gz

In Listing 5, we use the ls command to show the content of the dist directory.

The wheel binary package (with .whl extension) has the platform information in its name: cp38 means CPython version 3.8, linux_x86_64 is the operation system and the architecture - same as Go’s GOOS and GOARCH. Since the wheel file name changes depending on the architecture it’s built on, we had to write some logic in Listing 1 on lines 08-10.

Now you can use Python’s package manager, pip to install these packages. If you want to publish your package, you can upload it to the Python Package Index PyPI using tools such as twine.

See example.py and Dockerfile.test-b` in the source repository for a full build, install & use flow.

Conclusion

With little effort, you can extend Python using Go and expose a Python module that has a Pythonic API. Packaging is what makes your code deployable and valuable, don’t skip this step.

If you’d like to return Python types from Go (say a list or a dict), you can use Python’s extensive C API with cgo. You can also have a look at the go-python that can ease a lot of the pain of writing Python extensions in Go.

In the next installment we’re going to flip the roles again, we’ll call Python from Go - in the same memory space and with almost zero serialization.